Physician, philanthropist, radical political reformer. Instrumental in adding the rights of initiative, referendum, and recall to the Los Angeles City charter and the California state constitution.

Physician, philanthropist, radical political reformer. Instrumental in adding the rights of initiative, referendum, and recall to the Los Angeles City charter and the California state constitution.

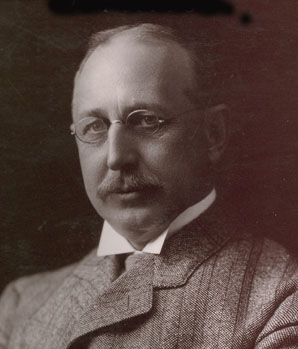

1853-1937. Born in Fairmont Springs, Pennsylvania, to parents of British descent. Haynes grew up in the state's anthracite coal region where his father, James Sydney Haynes, was a coal operator. His mother, Elvira Mann Koons, was of British and Dutch ancestry. On the British side her forebears arrived in America in 1635 and fought in the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

At the age of ten, John and his family moved to Philadelphia. The family fell on hard times and John went to work at 14. He became a carpenter's apprentice and worked his way through medical school, where he earned an M.D. and Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. He opened his own practice in a poor Irish and Jewish part of the city, where he developed a life-long sympathy for the plight of the poor. In 1882 he married Dora Fellows, a cousin from central Pennsylvania, who worked with John in the medical office and in his later reform endeavors. They had a son named Sydney who died of scarlet fever at the age of three. For health reasons, most of the Haynes family moved to Los Angeles in 1887, including his parents, his brothers Francis and Robert, and sisters Florence and Mary. All three brothers held MDs and at first lived together with their parents in a house at 8th and Main where they established an active medical practice. During the decade from 1880 to 1889 the city grew from 11,000 to 50,000 inhabitants.

In his first decade in Los Angeles John became personal physician to some of the most powerful families in the area: the Otis family who owned the Los Angeles Times, as well the Newmark, Rindge, and Rosecrans families. John became a director of the new California Hospital and practiced there after it opened in 1898.

In the same years John and Dora invested heavily in real estate and became extremely wealthy. They bought house lots, a commercial building in Monrovia, and a 2,700 acre ranch in Riverside County. John also had investments in two downtown theaters, in banks, the Union Oil Company, and the Pacific Railroad Company. He served on the board of directors of several local corporations and as director of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, 1895-97.

At the age of forty-four in 1897, John Haynes became a follower of the Christian socialist movement promoted by Reverend William Dwight Porter Bliss. This led to involvement in a long series of reform organizations. Bliss had founded the Union Reform League in San Francisco. John Haynes became a leader of its Los Angeles chapter, which soon also became the national office of the organization. The League's long-range goal was Christian socialism, but in the meantime it settled for immediate reforms: woman suffrage, direct legislation (the initiative process), public ownership of utilities, merit-based civil service hiring and promotion, graduated taxes, and other objectives of Progressive-era crusaders.

Though nominally a Democrat, John R. Haynes retained good friends among leading Republicans. With an unusual ability to bridge almost the whole political spectrum while remaining firmly at the left end, Haynes gave public support to the cause of socialism in Los Angeles. He became friends with millionaire socialist Gaylord Wilshire, the developer of Wilshire Blvd., and contributed to his journal "Wilshire's Monthly." He lent and then gave money to Job Harriman, an attorney from Indiana who ran for governor of California in 1898 on the Socialist Labor Party ticket and was Eugene V. Debs' vice presidential running mate in Deb's bid for the U.S. presidency on the Socialist Party ticket in 1900. And he donated to the Socialist Party directly and later to the Intercollegiate Socialist Society.

Haynes' most sustained effort was to win adoption for "direct legislation," which were the now familiar rights of ballot initiatives, referendums, and the right to recall public officials. Haynes viewed these reforms as a form of direct democracy that would weaken the power of special interests. His biographer writes that in the years after 1900 John Randolph Haynes became "the most significant reform figure in Los Angeles" (Sitton, p. 34).

Adding Direct Legislation to the Los Angeles City Charter

In 1900 Haynes was one of 15 members elected to an official city Board of Freeholders with the mandate of revising the Los Angeles City Charter. Through heavy lobbying of the other members he persuaded the board to endorse adding initiative, referendum, and recall, of which recall was then the most controversial. It did not exist in any U.S. city or state charter or constitution. The new city charter was approved locally but the State Supreme Court invalidated it. Two years later Haynes was able to revive the issue when a new Los Angeles charter revision committee was created. Though not a member this time, he sponsored an elaborate banquet for the members where prominent defenders of the reforms spoke. The committee agreed to support the direct legislation issues as amendments to the existing city charter. These were adopted in December 1902 by strong majorities in a citywide election. He next successfully lobbied the state legislature, which in that period had to approve changes in the Los Angeles charter.

Haynes and Gaylord Wilshire went to London in 1903 to meet with leaders of the Fabian Socialists. They had discussions with H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw. Back in Los Angeles, Haynes was appointed to the city's Civil Service Commission, where he served for twelve years, having special responsibility for the health and medical issues affecting city workers.

The first recall under the new Los Angeles ordinance took place in 1904 when labor groups and several of the city's smaller newspapers successfully removed an allegedly corrupt member of the city council, who had the backing of the Los Angeles Times -- the Times in those years was extremely right wing, antilabor, and hostile to the Progressive movement. This led to a personal break between Haynes and Times publisher H. G. Otis. Previously the Times had supported Dr. Haynes' reform campaigns, but from this point on it denounced him repeatedly and ran hostile political cartoons portraying him as inciting violence.

Haynes responded by making an alliance with William Randolph Hearst's Los Angeles Examiner. The Hearst press was famous for its sensationalist coverage, but in those years Hearst was also pro-union and backed numerous reform.

The Examiner also supported John Haynes' new interest in promoting city ownership of gas and electric utilities. In 1905 Haynes threw his support to City Engineer William Mulholland during the construction of the aqueduct system to bring water to Los Angeles from the Owens Valley. Mulholland had overseen the building of several electric generating plants along the aqueduct route where waterfalls could provide energy for power generation. Mulholland proposed that these continue to be city owned when the project was finished while the Los Angeles Times advocated that they be sold to private companies.

The San Francisco Earthquake, Legal Battles, a Trip to Russia, and Doctoring Clarence Darrow

On April 18, 1906, the famous San Francisco earthquake shattered the Bay Area. The same night Los Angeles city officials assembled a team of 25 doctors and 50 nurses to be sent by train to the beleaguered city. Dr Haynes was elected medical director of the team. They arrived in San Francisco by 1:00 pm the next afternoon. His biographer writes:

"In the midst of this chaos Haynes and his cohort established five makeshift hospitals to provide medical and surgical attention to the injured and to distribute food supplied to the Hearst organization. Haynes took charge of a hospital set up near Golden Gate Park that became the headquarters of the Los Angeles expedition. There he cared for whoever came in, and occasionally ventured out into the streets and rubble in search of those trapped and needing attention" (Sitton, p. 62).

That same year Los Angeles meatpacking interests mounted a lawsuit challenging standards imposed on them in a city initiative, arguing that laws made by ballot initiatives were unconstitutional. Haynes supported the City Attorney's defense of the law before the State Supreme Court, even hiring his own group of lawyers. The court upheld the Los Angeles ordinance.

Still later that year Haynes and a friend made a fact-finding trip to Europe that included spending time in Russia during the still-continuing revolution that had broken out in 1905.

On his return he served for three years as a clinical professor at the USC College of Medicine. At the end of 1907 he became Clarence Darrow's doctor. The famous lawyer had just returned from defending Big Bill Haywood and George Pettibone of the Western Federation of Miners in a bombing trial in Boise, Idaho. Darrow had an infection of the mastoid bone of his inner ear. Haynes assisted in an operation to remove the bone. Darrow took more than a year to pay his bill.

The Los Angeles Times' War with the Millionaire Socialist

The battle between Dr. Haynes and the Los Angeles Times became more bitter in 1908, as the Times printed scores of hostile cartoons of Haynes, denounced him as a dangerous crank, and in March attempted to tie Haynes to an alleged plot by Chicago "Reds" to murder the Los Angeles chief of police. The Times also threw its backing to a proposed bill that would allow the U.S. postmaster-general to permanently ban from the mails any publications deemed "improper," but particularly socialist and anarchist publications. Haynes wrote to every member of the California congressional delegation urging them to reject the repressive measure. "In this episode Haynes again had the last word, further infuriating the Times editors" (Sitton, p. 78).

The tenor of the Times campaign against Haynes can be gauged by its headline when his term as chair of the Los Angeles Civil Service Commission expired in February 1908: "Scandals During the Freakish Reformer's Regime Furnish Material for Grand Jury Investigation." Four other city newspapers refuted the Times' charges, and a new mayor reappointed Dr. Haynes to the commission chairmanship the following year.

Lincoln-Roosevelt Republicans Spearhead Progressive Reforms

For years John R. Haynes had systematically lobbied the state legislature personally and through paid lobbyists to adopt the three pieces of direct legislation that were his hallmark issue. These were blocked in Sacramento repeatedly by the extensive control over the legislators by the Southern Pacific Railroad. Ironically it was a revolt within the Republican Party that broke this logjam. In preparation for the 1910 gubernatorial elections a breakaway section of the state Republicans calling themselves the Lincoln-Roosevelt Republicans promoted a slate of anti-SP reform candidates lead by gubernatorial nominee Hiram Johnson. Haynes attended some of their meetings and cemented agreements that they would support his direct legislation proposals, although he did not join the Republican Party or participate further in their organization. He accepted an appointment to the Republican State Committee on Direct Legislation and helped to draft the amendments on those issues.

Hiram Johnson and the Lincoln-Roosevelt Republicans were elected in a landslide. In the 1911 session of the California legislature their draft constitutional amendments passed by the legislature and were put on the ballot for an October 1911 vote. They would establish initiative, referendum, and recall, as well as women's suffrage, workmen's compensation, and regulation of the railroads and public utilities.

The "Father of Initiative, Referendum and Recall"

John Haynes, through the Direct Legislation League which he headed, heavily financed the campaign to win support for the pending constitutional amendments. Dr. Haynes made a personal thirty-day speaking tour of the state. The amendments were approved by the voters in October. Thereafter John Randolph Haynes became known as "the Father of Initiative, Referendum, and Recall."

From 1911 on John Haynes, already 58, withdrew further and further from the practice of medicine to devote his time to public service. He campaigned for improved working conditions in mines on the national level, and was one of the very few of the upper-class reformers who championed unions and workers' rights. Governor Hiram Johnson appointed Haynes a special commissioner to investigate mine safety in the U.S. He also worked to establish the minimum wage in California and shorten the work day. He served for years on a state commission to reform prisons and mental institutions, and in Los Angeles worked to increase affordable housing.

A Grand House in West Adams

In 1912 he and Dora built a large house on the east side of Figueroa just north of Adams Blvd. in West Adams, just across the street from the Doheny compound at Chester Place. The architect was Robert D. Farquhar, who designed a two and a half story French-Norman chateau. Haynes' biographer describes the house as "one of the city's most stately residences of the time," with "a richly appointed interior of fine woods, silk damask panels, and exquisite furnishings" (Sitton, p. 128). Visitors included novelist Upton Sinclair, a long-time friend of Haynes. Back in 1905 Haynes had helped subsidize Sinclair's novel "The Jungle," the famous expose of the Chicago meatpacking industry.

During World War I Dr Haynes served prominently in state relief and war support efforts. In this period he broke with the Hearst press because of its antiwar and somewhat pro-German editorial policies. He several times during the war served as a local, state, or federal mediator in strikes or threatened strikes, where he generally took the side of labor rather than management. By the end of the war Haynes had shifted his priorities from direct legislation to public ownership of industries.

The 1919 Red Scare and Post-World War I Politics

In the Red Scare of 1919 Dr. Haynes was subpoenaed by a local grand jury to testify about his support of socialist causes. He feigned illness and refused to appear. The Los Angeles Times denounced him repeatedly as a "parlor Bolsheviki." Haynes got a comeback when Times publisher Harry Chandler invested in a joint effort with the Soviets to develop oil fields in Siberia. Haynes in an open letter challenged Chandler to explain how he could "enter into a business deal with Lenin, a man you had been daily denouncing as a blood thirsty fiend."

Despite the hostility of the L.A. Times, Haynes returned to prominence in the post-World War I period. He headed the gubernatorial campaign committee of William D. Stephens in 1918, a Republican Party progressive on some issues. After Stephens was elected Haynes was appointed to the State Committee on Efficiency and Economy, where he spearheaded a major simplification of California government, finally consolidating some 70 agencies into 5 departments. Stephens also appointed Haynes as a Regent of the University of California, an appointment unsuccessfully challenged by Stephens' successor as governor, right-wing Republican Friend Richardson.

City Ownership of Water, Gas, Electric Utilities

John R. Haynes, probably the city's leading advocate of public ownership of water, gas, and electric utilities, was appointed to the Los Angeles Public Service Commission in 1921 and served for sixteen years. In the early 1920s Haynes, working both as a commissioner and through private lobbying organizations, was instrumental in getting the Edison Company and the Los Angeles Gas and Electric Company to sell their distribution facilities to the city.

In 1924 Haynes was a leader of the independent Progressive Party presidential effort of Robert La Follette, which in California had to run on the Socialist Party ticket to gain ballot status. Haynes denounced the Democratic nominee John W. Davis as a corporate mouthpiece and the Republican, Calvin Coolidge, as a "moron."

Another of his causes was the construction of Boulder Dam. Haynes promoted the dam itself and the proviso that the electricity it generated would be sold to the city rather than to private companies. The dam was not actually built until the early 1930s, but Haynes was instrumental in winning public support for the project, which was opposed by the Los Angeles Times, reportedly because publisher Harry Chandler owned thousands of acres of farmland in Mexico that would be less profitable if the dam helped to irrigate California's Imperial Valley (Sitton, p. 176).

The John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation

Reaching their early seventies, John and Dora began to consider how to preserve their considerable fortune -- some $2 million -- to continue after their deaths to promote causes they supported. In September 1926 they cofounded the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. The foundation was committed to enhancing democracy and promoting public ownership of utilities. Another goal was improving the living conditions of workers. On this score Haynes was particularly concerned with mine safety.

Haynes committed the foundation to several other causes, although the directors he chose generally avoided funding them. These included his support to the then-fashionable eugenics movement, which called for selective breeding of humans and preventing the "feeble minded" from reproducing; endorsement of Prohibition; and support to Margaret Sanger's birth control organization. Haynes was also a major supporter of the American Indian Defense Association.

In the mid-1920s Haynes, as one of the four University of California Regents based in Southern California, was intimately involved in the construction of the Westwood campus of UCLA, which began in 1927, and the transfer of the university there from its Vermont Avenue campus in 1929. Dr. Haynes put up some $25,000 of his own money to help purchase the Westwood land, and was a major donor to the original UCLA library.

Battles over Public Ownership of Water and Power Utilities

In preparation for the construction of Boulder Dam, Los Angeles in 1928 created the Metropolitan Water District, entrusted to build the Colorado River aqueduct to bring water to Southern California. Haynes, already a city Department of Water and Power commissioner, was appointed to the MWD board, where he worked to safeguard DWP interests in this broader Southern California forum.

Haynes and city ownership of water and power utilities came under sharp attack during the administration of Mayor John C. Porter (July 1929-July 1933). Porter, a protege of the fundamentalist minister, Ku Klux Klan supporter, and anti-Semite publicist Robert Shuler, packed the DWP board with supporters of private electric companies who sabotaged its work. A major political battle erupted in the city, in which supporters of municipal ownership succeeded in winning a majority on the city council. The new city council refused to confirm three consecutive appointments to the DWP board by Mayor Porter. Porter dismissed Haynes as president of the DWP board, but the city council refused to approve the action and it failed. Haynes, at 79, continued in office.

Dr. Haynes played a large part in selecting Frank Shaw to run, successfully, against Porter in the 1933 elections. Shaw was later recalled, in 1938, in a series of corruption scandals and revelations of criminal activity by members of the LAPD, the first such recall in a major U.S. city. But in 1933 he had a reputation as a progressive and was active in providing jobs for the unemployed. He supported municipal construction projects to aid both the city and the large number of workers suffering from the Depression.

Haynes acted as an advisor to Shaw and helped to secure the appointment of many public officials committed to city ownership of utilities and other reforms. During the two-term Shaw administration the city completed its independence from private water and electric companies, most importantly through the completion of Boulder Dam, now renamed Hoover Dam, which began to furnish electricity to the city in October 1936. The conversion to all-city-owned electric power was completed at the end of 1937. The Los Angeles Times, a bitter opponent of public ownership, built its own generators in its building's basement and refused to buy electricity from the city-owned utility.

The Haynes Foundation after the Deaths of John and Dora Haynes

John Randolph Haynes died on October 30, 1937, at the age of 84, still in office as president of the Board of Water and Power Commissioners. Flags on all city buildings were flown at half mast. Dr. Haynes was buried at Rosedale Cemetery next to Dora, who had died in November 1934.

The Haynes Foundation, which had become moribund in the first years of the Depression, revived after Dora's death. The foundation received $140,000 at the settlement of her estate in mid-1935. On John's death the majority of his wealth passed to the foundation as well. Under the administration of his nephew Francis Haynes Lindley the foundation drew back from activist progressive political causes and turned instead to support of research and community forum programs. It used the Figueroa and Adams Haynes home as its headquarters until 1952 when the building was demolished to construct the Harbor Freeway.

The John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation today is located at 888 W. Sixth Street, Suite 1150 in Los Angeles. It continues to fund social science research about Los Angeles, awarding grants of some $3 million each year. Its special concern is social problems in the city of Los Angeles.

from the biography "John Randolph Haynes: California Progressive" by Tom Sitton